Can A Registered Sex Offender Travel To Mexico

Argument preview: When a sexual activity offender moves out of the country, does he have to tell anyone?

on February 23, 2016 at 11:29 am

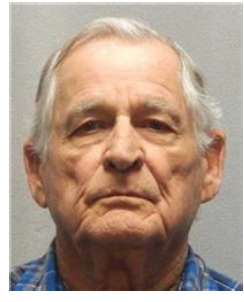

When Lester Ray Nichols, a federally convicted sex offender, left Kansas in 2012 to go live in the Philippines, one might accept thought the United States government would be happy to encounter the back of him. Not so. Federal authorities tracked him down in Manila and escorted him back to Kansas, where he was convicted in federal district courtroom of failing to notify Kansas regime that he had left the country. On March 1, the U.S. Supreme Court volition hear his argument that his motion never triggered a duty to notify anyone.

Nichols's case turns on the interpretation of the Sexual activity Offender Registration and Notification Human action (SORNA). Two SORNA provisions are in play, 42 U.S.C. § 16913(a) and (c). They state (in pertinent part):

(a) A sex offender shall annals, and go on the registration current, in each jurisdiction where the offender resides, where the offender is an employee, and where the offender is a pupil.

(c) A sex offender shall, not later than 3 concern days afterwards each modify of proper noun, residence, employment, or pupil status, appear in person in at least ane jurisdiction involved pursuant to subsection (a) and inform that jurisdiction of all changes in the information required for that offender in the sex activity offender registry. That jurisdiction shall immediately provide that data to all other jurisdictions in which the offender is required to register.

Nichols was convicted of failing to notify Kansas of his motion to the Philippines on the theory that, at the moment he "changed" his "residence," Kansas was notwithstanding the jurisdiction where he resided. If he had been moving to another SORNA jurisdiction (such as another U.S. state), he could have satisfied his statutory obligation past registering there within three business days. Because the Philippines is non a SORNA jurisdiction, however, Kansas was the only jurisdiction he could have notified. The U.Due south. Courtroom of Appeals for the Tenth Excursion affirmed his conviction on the strength of its 2011 two-to-one console decision in a materially indistinguishable instance, U.s. v. Murphy.

The crux of Nichols'southward statement is fairly simple. Nether Section 16913(a), a modify in residence ordinarily triggers a duty to notify the jurisdiction to which the person is moving. Because the Philippines is not a SORNA jurisdiction, however, he was not required to notify the Philippines. And because Kansas was no longer his residence, he was non required to notify Kansas, either. According to Nichols, the government could not have it both ways: if his abandonment of Kansas triggered a duty to notify, then Kansas could no longer count as his electric current residence. Once he abased Kansas with the intent to stay habitually in the Philippines, the Philippines became his current residence.

The authorities responds that, even following abandonment, Kansas "necessarily remain[ed] 'involved pursuant to subsection (a),' because the offender continue[d] to announced on its registry as a current resident." In order to be owed a notification, Kansas demand not accept been Nichols'southward residence, it merely needs to have been a jurisdiction "involved" within the meaning of Section 16913(a). Although the authorities cites the Tenth Circuit'due south opinion in Murphy as authorization for this proffer, it would hardly exist surprising if the Justices press the government on whether the mere fact that Nichols'southward name connected to announced on Kansas's registry was enough to maintain Kansas's status equally an "involved jurisdiction."

Nichols asserts that the overriding purpose of SORNA is to protect children where a sex activity offender currently resides, not children who alive in his by residences. The regime seemingly struggles to come up with reasons why Congress would take wanted notification given to the jurisdiction being vacated. "An offender who has absconded may pose no directly continuing threat to his erstwhile neighborhood," states the authorities, "but customs members should non make decisions about where to alive or ship their children – either for school or for an afternoon playdate – on the basis of obsolete data creating a misimpression that absent offenders notwithstanding reside in the area."

Nichols also argues that authorities demand not rely on an offender'south notification that he is leaving the state, since he volition have used his passport to travel internationally. The authorities's response, aside from expressing skepticism that offenders volition reliably written report passport information, is that cognition of an offender's international travel and knowledge that the offender has actually abandoned his U.S. residence are not the same thing. "The government should not bear the onus of continually evaluating, as the sexual activity offender's international sojourn lengthens, whether his address of record should be retained on the rolls as his 'electric current' registration information. The offender himself should simply requite notice at the start that he is moving."

To bolster its point that authorities should not be kept guessing, the government recounts the constabulary enforcement backwash of Nichols's departure from Kansas. "Betwixt November 16, 2012 and January 17, 2013, the investigation of petitioner'south . . . disappearance involved federal probation officers, a federal-courtroom warrant, the Land Department'due south Diplomatic Security Service, the Manila Police Department, the Philippine Bureau of Immigration, and the U.s.a. Marshals Service," states the government's brief. "None of that would accept been necessary if petitioner had taken the simple stride of advising Kansas of his alter of residence." 1 wonders if that last judgement might involve overstatement. Would the authorities really take a sex offender's representation that he has left the country at face value, with no independent verification?

Viewed as a whole, the government's master concern seems to exist that a reversal of Nichols'southward confidence would recognize and thereby implicitly sanction a "leaving the country" loophole in SORNA's notification coverage. From the outset, the government's brief hammers the signal that Congress has continually sought to augment the system of sex-offender registration and notification. The Wetterling Act of 1994 used federal funding to encourage states to prefer certain minimum standards in their sex-registration laws. In 1996, Megan'due south Constabulary added a mandatory community-notification provision. That same year, Congress directed the FBI to create a national sex-offender database. In the immediate years following, Congress continued to enhance federal registration and notification requirements.

But Congress became convinced that all this was non enough. "Loopholes and deficiencies" in the registration and notification systems led to an estimated 100,000 sex offenders becoming "missing" or "lost" – out of a total of 500,000. This, in 2006, led to SORNA, which was intended to make "more compatible and constructive" the "patchwork" of federal and state sexual practice-offender registration systems then in effect. By so prominently recounting this history of legislation, the government'due south brief clearly means to chronicle a congressional feet virtually the existence of gaps in the registration and notification authorities.

If the Court rules in favor of Nichols, does that mean any sexual practice offender can escape SORNA simply by moving to some other country? Tune Brannon, Nichols's federal public defender from Kansas City, can certainly look that question before she gets very far in her argument. If she sticks to her brief, her answer volition be a frank "yes." A sex offender who moves to some other country is no longer a threat to children in the U.s.a., and SORNA but protects children in the United States. If the offender returns to the Usa, his SORNA obligations immediately resume. Thus, there is no "gap." Nichols's brief goes then far every bit to argue that a sex activity offender who has left the country is no different from a sex offender who has died – at to the lowest degree for purposes of electric current SORNA obligations. Leaving the state unannounced may identify some brunt on authorities to figure out where the offender has gone, but and then does leaving the globe unannounced.

The government rejects the analogy. "A sex offender who is traveling abroad is hardly, equally petitioner posits, 'coordinating to a sexual activity offender who has died.'" This is considering "state and local authorities typically acquire adequately quickly when a resident has died and may easily make up one's mind whether he is a registered sex offender.". In whatever event, continues the government's brief, it would be and then easy to maintain the comprehensiveness of the registration and notification arrangement if the Courtroom were simply to rule that sex activity offenders must notify the authorities in their residence jurisdiction earlier they leave the land. "Given the ease of protecting the sex activity-offender registry's integrity from corruption with obsolete information, it would indeed come up as a 'surprise' if SORNA were construed equally not requiring a sex offender to give observe when he moves to a strange land."

The regime's chances thus seem to depend upon the Court'southward receptiveness to the assertion that the purpose backside SORNA is to create a organisation that keeps track of sex offenders in every conceivable mode, including when they are no longer in the United States. Not just must the Justices accept that premise, but they must agree that the Court is the appropriate body to fill up out a statute that does not address the effect in so many words. The empty seat of the late Justice Antonin Scalia will undoubtedly grab the corner of every eye as this classic case of statutory interpretation is debated.

Recommended Commendation: Evan Lee, Argument preview: When a sex offender moves out of the country, does he have to tell anyone?, SCOTUSblog (Feb. 23, 2016, 11:29 AM), https://www.scotusblog.com/2016/02/argument-preview-when-a-sex-offender-moves-out-of-the-state-does-he-accept-to-tell-anyone/

Can A Registered Sex Offender Travel To Mexico,

Source: https://www.scotusblog.com/2016/02/argument-preview-when-a-sex-offender-moves-out-of-the-country-does-he-have-to-tell-anyone/

Posted by: holleybirear.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Can A Registered Sex Offender Travel To Mexico"

Post a Comment